Pages 11–12

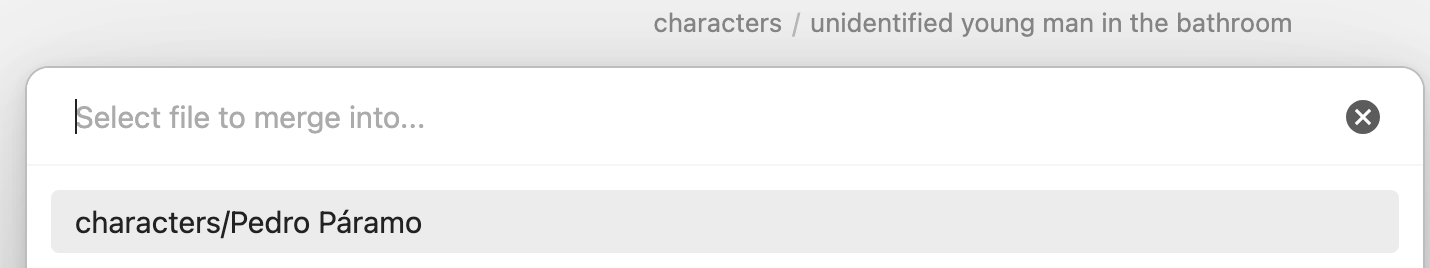

We identify the young man who is the new main character (still nothing on the old main character)

Previously, Pedro Páramo completely changed gears to a different time with different characters and even different punctuation.

Pages 11–12

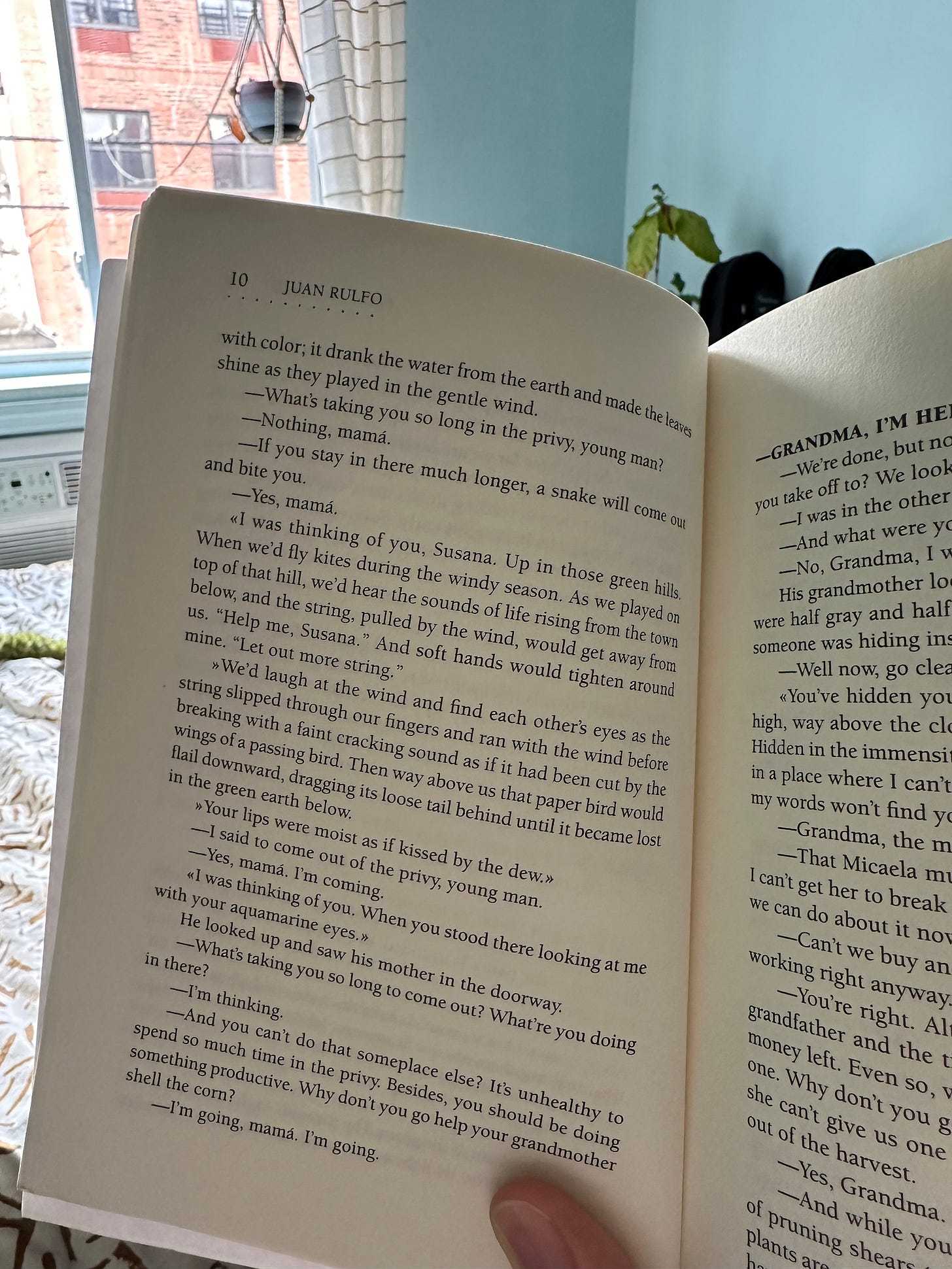

Another passage with seemingly two different narrators jostling to narrate the story. The story of a young man who was tasked with helping his grandma with an errand she already finished.

His grandmother looked at him with those eyes of hers that were half gray and half yellow and that seemed to know what someone was hiding inside.

–Well now, go clean out the mill.

«You’ve hidden yourself away, Susana, hundreds of meters high, way above teh clouds, farther away than all other things. Hidden in the immensity of God, behind His Divine Providence, in a place where I can’t reach out, nor even see you, and where my words won’t find you.»

–Grandma, the mill’s not working, the grinder’s broken.

Lots to unpack here, albeit entirely in the guillemets from presumably the young man, presumably talking from his future as Old Man (who I’m just guessing is Pedro Páramo, speaking from the present with the unnamed main character where by that point he’s a ghost [which I guess would make him Dead Man]). Previously, all the detail of his time with Susana was innocent kite-flying fun, but now she sure sounds dead. Unless… guillemet narrator is interrupting to note that Susana is dead during his time?

Now, sure, you might be thinking, “god, Matthew, just keep reading the book. You’ll probably get an answer if you read more than four sentences at a time.” But Pedro is just picking up, you guys. It never gets clearer without getting more convoluted first:

Grandma complains that Micaela (whoever that is) must have broken the grinder in the mill and tasks the unidentified young man with going to town to get a new one, which they’ll have to pay for on credit out of the upcoming harvest, because his grandfather just died and it cost most of their money to bury him. Which means I have yet another character note that just looks like this:

The young man spends the rest of this section getting fetch quests from NPCs. Grandma tells him to get a grinder, sifter, and pruning shears from doña Inés Villalpando. He finds 24 centavos on a shelf and takes 20 of them. He runs into his mom who asks him to get a meter of black taffeta and cafiaspirina pills as long as he’s running errands. She tells him to take money from the flowerpot to do so, where he takes a peso and leaves behind the 20 centavos he found earlier.

THEN IT ALL GOES TO SHIT.

«Now I’ve got enough money for whatever I want,» he thought.

–Pedro! –they yelled after him–. Pedro!

But by then he couldn’t hear a thing. He was already a long way off.

OK LOTS TO UNPACK HERE. Obviously, 1) the reveal that this is, in fact, young Pedro Páramo. Good lord I have a lot of notes to retitle. 2) Pedro’s little money movements seem weird and arbitrary, but when you remember this is a story about how landlords are assholes, yeah, now that we know this is Pedro, whatever he’s doing is sus. But most perplexingly, 3) why are his thoughts in guillemets? Are the guillemets merely thoughts and not a competing narrator who is Pedro reflecting from the future? Christ, we gotta go back to the previous section to see if this new theory tracks.

WELL… I GUESS? Maybe the guillemets are just, like, the Dune thing where every character’s inner voice is italicized throughout. Maybe the guillemets are just text that, more contemporarily conventionally, would be italicized. Dang, maybe we cracked the mystery of the guillemets after all? (I doubt it. It’ll definitely get weird again.)

ALSO weird and important during these two pages, the third-person narrator (not the guillemet not-narrator) tells us that “You could hear [the hummingbirds’] wings whirring among jasmine bushes that had bent over from the weight of their flowers.” This may not sound important, but isn’t it interesting that the third-person narrator – the one who seems the least definitely a character – referred directly to “you”, the reader? Think about it, instead of writing “one could hear” or “a person could hear”, the choice was made to say “you”, positioning this narrator as an entity addressing a third party of whom the narrator has awareness. A narrator who remains an ethereal voice without body or motive in this world reaches across the pages themselves to tell the person holding the book what they could see if they were there? ISN’T THAT WEIRD? Have I lost perspective of what is weird? Already?! On page twelve?!!!

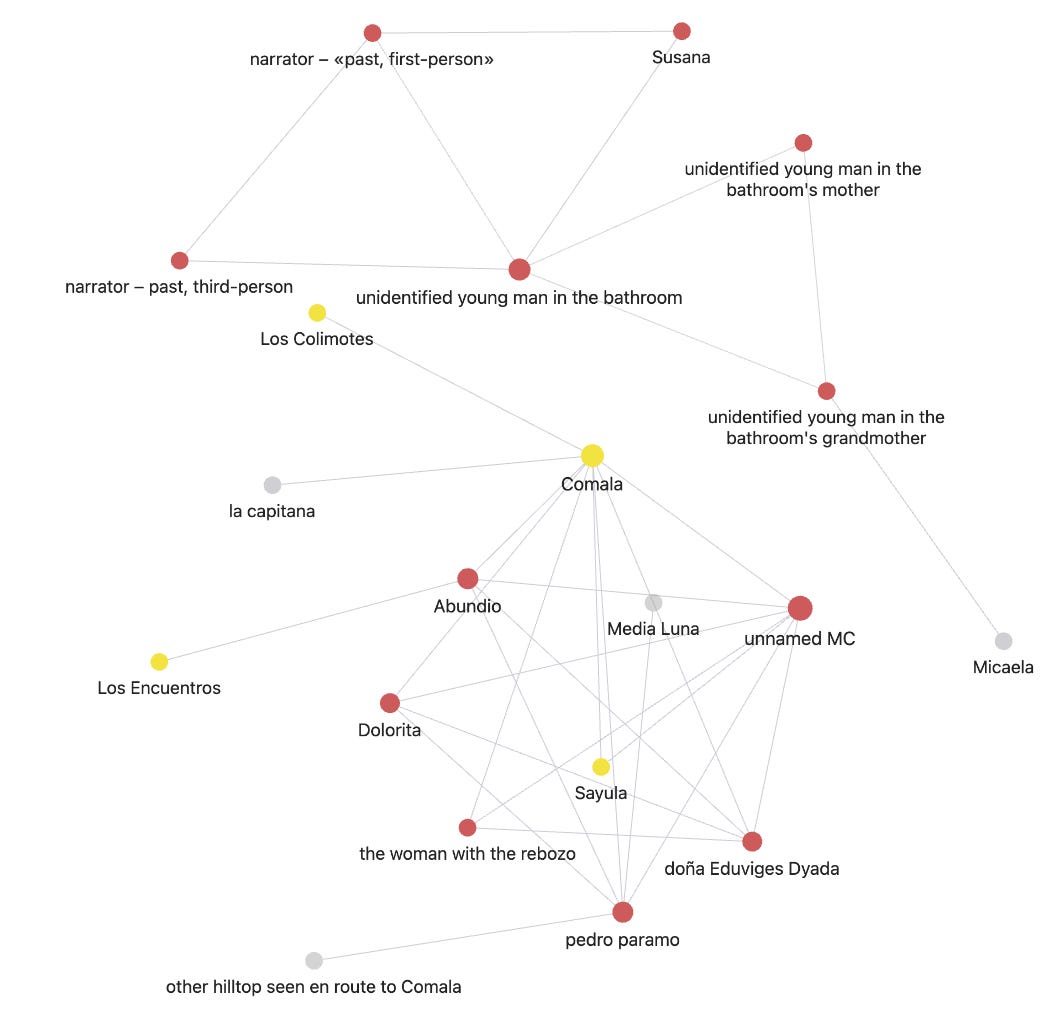

How’s Obsidian looking?

I guess it’s time to figure out how this feature works:

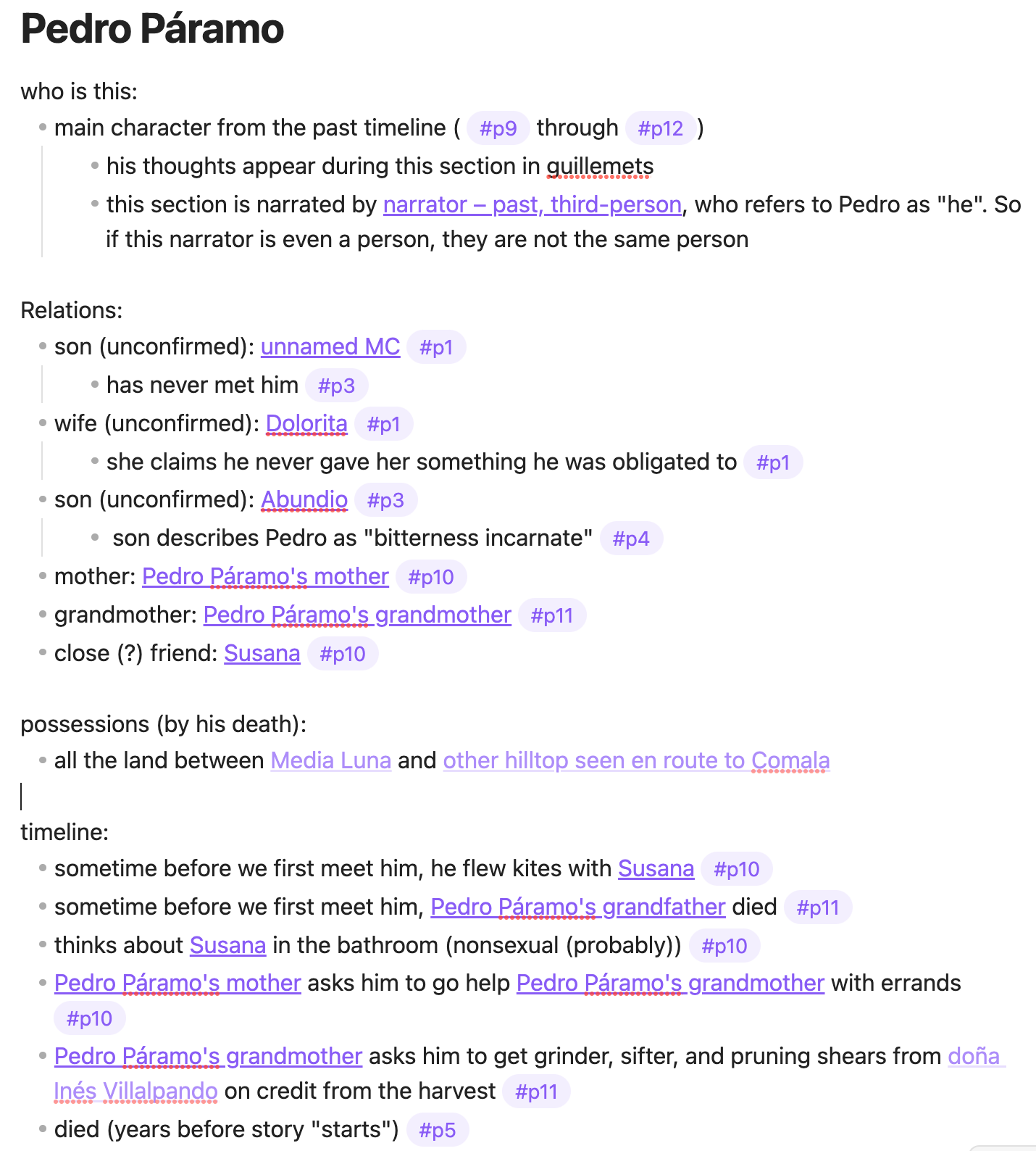

It turns out it just adds the text of the note to be merged to the bottom of the note it’s merging with. And, crucially, updates all the links elsewhere to be to the merged-with note. Neat! After moving around the details to the same sections manually (there’s probably a more automatic way to do that, but given how organically these notes need to grow to make sense of this book, that’ll probably be more organizational trouble than it’s worth), we have… a very, very partial tale of the life of the man known as Pedro Páramo:

I kind of love that all we can say for certain about anything that happens in Pedro Páramo is that, eventually, everyone dies.

As we wrap up today’s post, I would like to share something beautiful with you:

It’s all coming together.

tl;dr wtf happened in Pedro Páramo today

We learn that the shift is indeed a flashback to a young Pedro Páramo, which is being narrated by some third-person narrator of unknown entity and is being «thought about» by Pedro himself. Pedro gets some chores to do.

«If you’re feeling a little lost missing out on every third post and wishing you hit up that moving sale that ended last week, I have good news for you. Welcome… to the regret sale.»