Yes, fate is cruel. FIVE pages! Today’s is the biggest post ever, and yet it is one of the every-third-post, paid subscribers–only posts. Perhaps you regret missing out on the earlier sale. Perhaps you regret the opportunity slipped by to get access to all posts at the lowest price possible, to say nothing of supporting this little recap blog project, for less than $10/year. It seems that Pedro Páramo’s titular Pedro Páramo will have something to say about regret at the end of all of this, but, alas, ironically, without full access, how will you know? Much to regret in this life. Such as missing a sale, definitely.

Previously, we took a detour from our as-yet-unnamed main character who had gone to a ghost town in search of his long-lost father, Pedro Páramo, and got a mysterious flashback to a young Pedro Páramo and his longing for the maybe-dead Susana. Today, one of the book’s longest sections, we return to our as-yet-unnamed main character.

Pages 13–18

Whatshisname is staying with the still alive doña Eduviges, who offered him a guest room, claimed she got a telepathic message form his mother that he was coming (nevermind that, in addition to how that’s impossible already, she’s also dead), and, oh, by the way…

–Yes, it’s true, I was close to being your mother. She never told you?

–No. She only told me good things.

lol savage

–I heard about you from the muleteer who brought me here, a man named Abundio.

Who also claimed to be your half-brother and you had absolutely no reaction to learning you had another relative out there, but there’s a lot going on right now for you, our unnamed main character. Who I suspect is not going to be our main character for long.

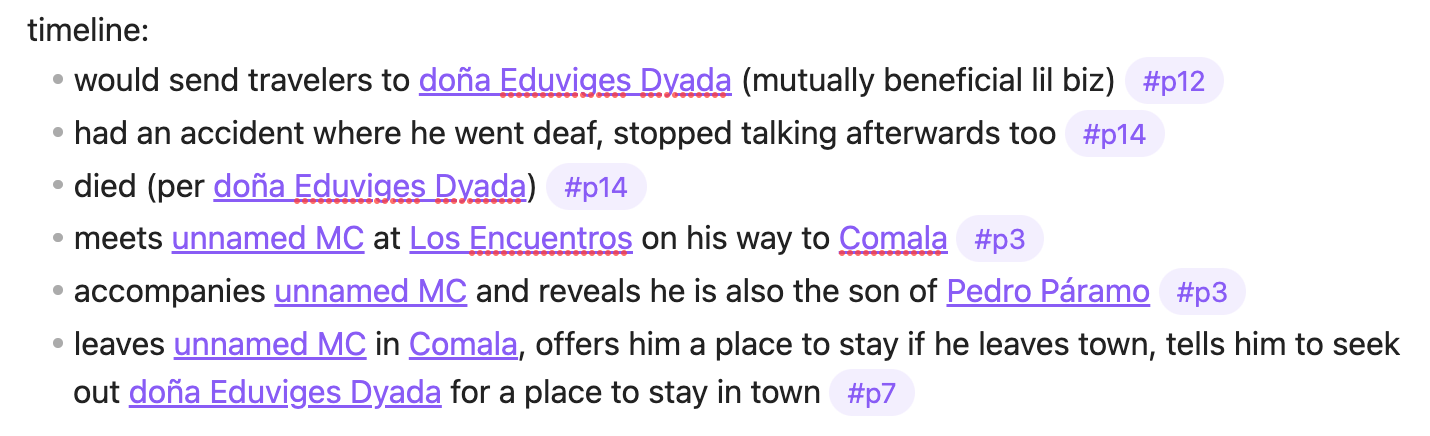

doña Eduviges explains that Abundio used to bring travelers her way and she’d compensate him a little, but “the times have changed, and nobody keeps in touch with us now that things are so much worse around here.” (“Worse” meaning, for those keeping score at home, she is one of two living people her guest has seen in town all day.) She goes on to sing the praises of Abundio, ominously referring to him in the past tense, and we can see where this is going.

–After [the accident], he stopped talking, even though he wasn’t actually mute. In any event, he kept on being a good person.

–The one I’m talking about could hear just fine.

–Must not be him, then. Besides, Abundio died already. He must have died already. So you see? It couldn’t have been him.

–That sounds right.

Probably what this means is they’re realizing, “huh, must’ve been a different Abundio, then.” But I like how it’s not implausible to think that what our unnamed main character means is that, even at this early point, he’s already full-on like “sure, yeah, I talked to a dead person. That sounds right.” At any rate, following these updates to Abundio’s note, we have yet another Obsidian note where “died” is in the middle of someone’s timeline, as if of no consequence.

doña Eduviges tries to get back on track to what she means about this whole “I should’ve been your mom” business (ie, the good stuff). She tells him about a man named Inocencio Osorio who used to work “taming horses” at the Media Luna. “Taming horses” is in quotes in her tale; while this is meant literally, it’s also meant metaphorically.

–he plied another trade: that of “provocateur,” arousing people’s fantasies. That’s what he really did. And he drew your mother in like he’d done with so many other women. Myself included.

She tells a tale of how Inocencio would seduce women by offering massages which just got too darn sexy, somewhere between silver-tongued and more than a little nonconsensual-sounding. Also, as a bonus, after “he’d have you all heated up”, he would also “talk about your future” and “fall into a trance and roll his eyes while chanting and cursing”. The man knew what women want, apparently.

doña Eduviges suggests that while women knew his trances predicting the future were bullshit, the reason why any of this is relevant to our story at all is because of an important time it was ominous enough.

»As it turns out, when [your mother] went to see him, this Osorio guy gazed into your mother’s future and told her she “should avoid lying with a man that night, since the moon was fraught with danger.”

»Dolores came to me all worked up saying she couldn’t do it, that there was no way she was gonna sleep with Pedro Páramo that evening. It was her wedding night. And there I was trying to convince her she couldn’t trust Osorio, that he was little more than a two-faced con artist.

Then things get crazy. Punctuation-wise and plot-wise! What a treat!

»–I can’t –she told me–. Go in my place. He won’t notice.

JUST A NORMAL FAVOR TO ASK YOUR FRIEND! “Hey, please pretend to be me and fuck my hsuband on our wedding night, because the town amateur masseuse/fortune teller who tries to fuck his clients told me a spooky fortune. Look, he won’t even notice, just do this for me.”

»Needless to say, I was quite a bit younger than she was. And not as brown, but that’s not something you notice in the dark.

»–It’s not gonna work, Dolores, you’ve got to go yourself.

»–Do me this one favor. I’ll pay you back with others.

doña Eduviges reveals to the unnamed main character that what Dolores didn’t know what that she had a thing for Pedro Páramo anyway. Sort of explaining why this messy bitch goes along with this insane plan, she sneaks into bed with Pedro under the cover of darkness, but nothing happens.

»the day’s excitement had left him worn out, and he spent the night snoring. The only thing he did was to intertwine his legs with mine.

The next day they wake up early and switch back. Dolores asks doña Eduviges what her husband did to him (seems like a question you already know the answer to), and doña Eduviges explains that she’s “still not sure”. Kind of seems like the best outcome, really.

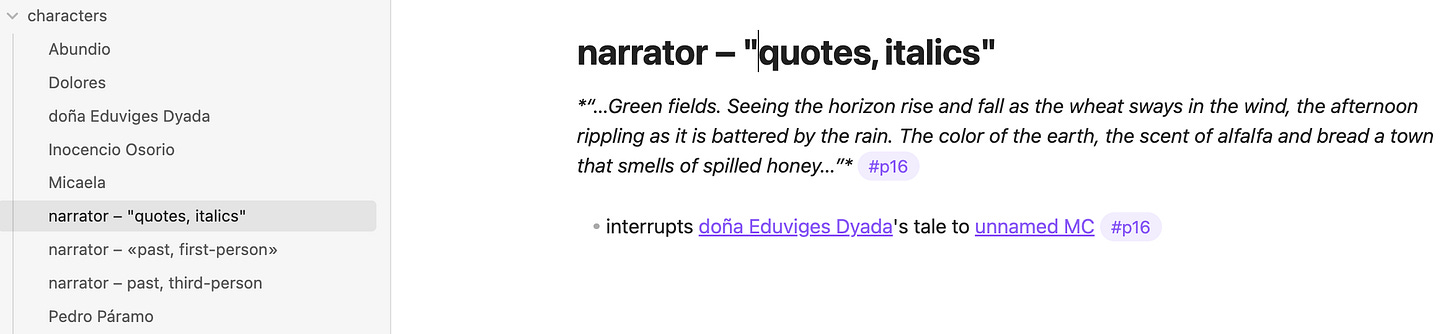

doña Eduviges’s tale skips ahead. The unnamed main character is born the following year. Some myserious quotation marks and italicized text interrupt and I can’t begin to guess who is saying this or from when.

»Maybe your mother was too ashamed to tell you any of this.

“…Green fields. Seeing the horizon rise and fall as the wheat sways in the wind, the afternoon rippling as it is battered by the rain. The color of the earth, the scent of alfalfa and bread a town that smells of spilled honey…”

»She always loathed Pedro Páramo. “Doloritas! Did you tell them to get my breakfast ready?”

So. It’s not in guillemets, which I think means we can safely assume it is not doña Eduviges. Let’s consider the various combinations we have from this section alone to try to pick this apart. Time for a new feature on wtf is pedro páramo, I guess, which we’re going to call:

«Punctuation Junction»

EXAMPLE THE FIRST:

–Yes, it’s true, I was close to being your mother. She never told you?

Present day dialogue. Easy peasy.

As I listened to her, I began to pay closer attention to the woman standing before me.

Normal narration. In this section, it’s even from a known character. Easier peasier.

»As it turns out, when she went to see him, this Osorio guy gazed into your mother’s future and told her she “should avoid lying with a man that night, since the moon was fraught with danger.”

doña Eduviges’s tale. You’d think this would be in dashes, since she’s saying this out loud to the unnamed main character. But, furtherly curiously, this is distinct from our previous guillemet adventures, because this is a closing guillemet with no opening guillemet. So it still sort of tracks that this isn’t breaking the rules yet! Maybe this is a new thing that doesn’t contradict our current theory of the guillemets that they’re interior thoughts belonging to a non-narrating character. Although I suppose even that could still work if, say, she were merely thinking this rather than saying this out loud to the unnamed main character, who is the narrator of this section! The only thing we know for certain about the trajectory of this book is that time and reality break down in this town as it becomes a swirling nonlinear narrative in which the dead interrupt with their stories. So insofar as that makes sense… this makes sense.

And then the quotation marks are just dialogue told during this narration. Like single quotation marks inside double quotation marks in contemporary, normal, non–meaning-obscuring prose. Or, in Pedro-land:

»–I can’t –she told me–. Go in my place. He won’t notice.

Same same but different. Another character’s dialogue inside of a nonnarrating character’s… thoughts, maybe, if she isn’t still speaking out loud? lol, I thought this was one of the easy ones, but idk why it wouldn’t just be –“I can’t,” she told me. if so… so… I don’t know.

“…Green fields. Seeing the horizon rise and fall as the wheat sways in the wind, the afternoon rippling as it is battered by the rain. The color of the earth, the scent of alfalfa and bread a town that smells of spilled honey…”

I GOT GODDAMNED NOTHING. Best guess is this is yet someone else entirely, just interrupting with their ghost voice. Maybe Dolores herself. I guess we have to put a pin in this observation and see if anyone later makes this same observation, so we can see how time and space are breaking apart, I think? Why not. We’ve already got two other narrator-characters who may not even be characters.

Pages 13–18, continued

doña Eduviges’s tale moves forward to describe a troubled marriage. Pedro always complained to Dolores, she always loathed him. One day, the three of them were hanging out and saw a vulture, and Dolores sighed and wished she were a vulture so she could fly away and visit her sister. Dolores and Pedro say goodbye to each other as she leaves town apparently forever.

»She left the Media Luna for good. Some months later, I asked Pedro Páramo how she was doing.

»–She loved her sister more than she did me. I’m sure she’s happy there. Besides, she was getting under my skin. I have no plans to ask about her, if that’s what you’re getting at.

»–But how will they survive?

»–Let God take care of them.

“…Make him pay dearly, my son, for having abandoned us.”

»And that was the last we heard from her until now when she let me know you’d be coming to see me.»

HOLY SHIT, IT IS THE MOM INTERRUPTING FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE. That was the first thing she said, way back on the first page of the book! Wow, all I had to do was read another page to solve this mystery. Now leafing through the book again, we actually got this clue way back on page 6 when we first arrived in Comala:

Yes, filled with voices. And here, with the air so thin, they were easier to hear. They settled inside you, heavy. I remembered what my mother had told me: “You’ll hear me better there. I’ll be closer to you. You’ll find the voice of my memories closer to you there than that of my death, that is if death has ever found a voice.” My mother … The living one.

…ok, wait, I don’t know what he meant by “the living one” back on page 6 and I’m just going to improbably assume it’s not terribly important.

Having finished her tale, our unnamed main character starts to tell her what happened to Dolores after that, that the two of them lived with the sister, Aunt Gertrudis, for a while, but she would always ask why Dolores didn’t go back to live with Pedro. (Also, since we learned on page 3 that Dolores’s son says he never met his father, she must have left either when he was very young or possibly even before he was born.) We learn that Dolores refused to go back unless Pedro sent for her… but, once again, we learn this by means of a new little punctuation puzzle:

–A lot happened after that –I said–. We were living with my Aunt Gertrudis in Colima, but she felt we were a burden and rubbed it in our faces. “Why don’t you go back to your husband?” she’d always ask my mother.

»–Has he sent for me, by chance? I’m not going back unless he sends for me. I came because I wanted to see you. Because I loved you, that’s why.

Once again, this is dialogue in a closing guillemet. So while Dolores is saying this, it is unclear who is saying she said this. At first glance it seems like Dolores’s son, since he began this tale, but then why wouldn’t it just be in dashes and quotation marks again? My best guesses from breaking down this whole, long section are: 1) maybe the closing guillemet is just a continuation of the same person speaking in a new paragraph, like if a paragraph started with an opening double quotation mark (“) but didn’t end with a closing one (”), and the next paragraph started with another opening double quotation mark (“), since it’s harder to convey that nuance with a dash that looks the same forwards and backwards. It’s probably this. BUT. 2) It could be someone thinking this. The section ends not not suggesting it could be theory #2:

I thought that woman was listening to me; but I noticed her head was cocked as if she were hearing some distant sound.

Although I’m not sure if the sections narrated by Dolores’s son can include narration he is not privy to… or if there are any real rules in this book at all.

tl;dr wtf happened in Pedro Páramo today

The main character, who today has traveled to a ghost town to find his estranged father, met his mother’s friend from her youth, who tells him that his mom asked her to boink his dad for her on their wedding night because the town womanizer-slash-fortune teller said so. Somehow, their marriage was an unhappy one, and one day she unceremoniously left town forever.